Wed 31 Dec 2025 10.00 CET

In a 1924 letter to André Gide, Thomas Mann said he would soon be sending along a copy of his new novel, The Magic Mountain. “But I assure you that I do not in the least expect you to read it,” he wrote. “It is a highly problematical and ‘German’ work, and of such monstrous dimensions that I know perfectly well it won’t do for the rest of Europe.”

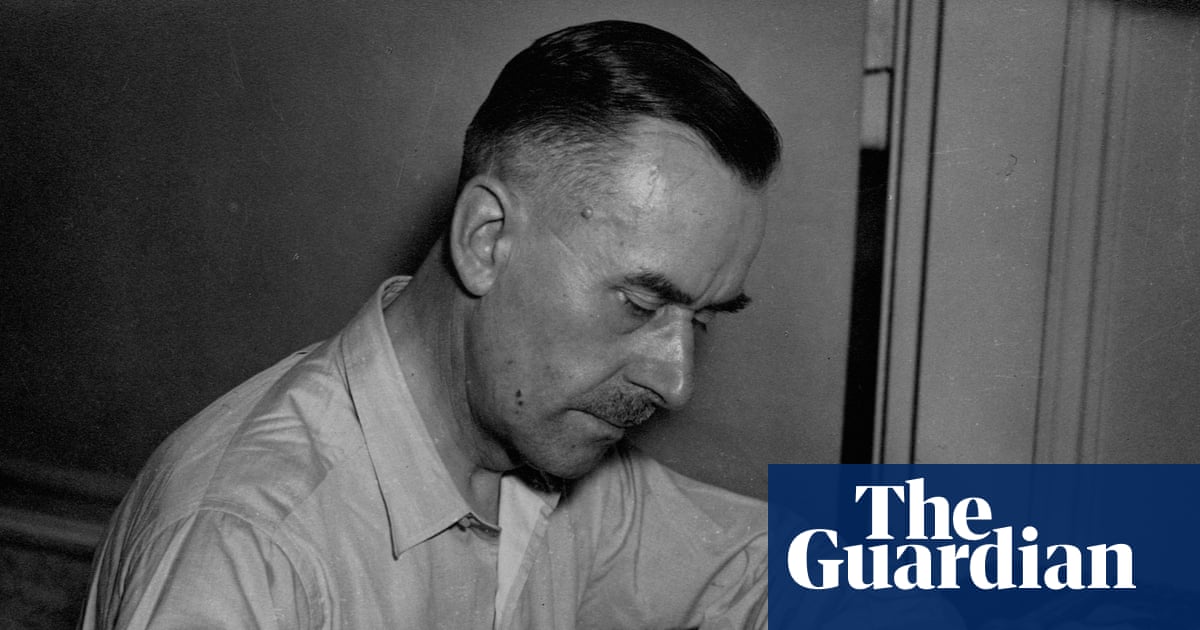

Morten Høi Jensen’s approachable and informative study of The Magic Mountain positions Mann as a writer who was contradictory to his core: an artist who dressed and behaved like a businessman; a homosexual in a conventional marriage with six children; an upstanding burgher obsessed with death and corruption. Very much the kind of man who would send someone a book and tell them not to read it.

Despite the doubts Mann expressed to Gide, The Magic Mountain – a very strange, very long novel – was embraced throughout Europe, and three years later in America, too. Its publisher there ignored the strangeness and proclaimed its “use value … for the practical life of modern man”. While that makes it sound like Jordan Peterson-style cod philosophy, in fact it stands alongside In Search of Lost Time, Ulysses, The Man Without Qualities and To the Lighthouse as one of the summits (apologies) of literary modernism.

The novel describes its youthful protagonist, Hans Castorp, visiting a tuberculosis sanatorium in Davos where his cousin is a patient. Intending to stay a few days, he doesn’t escape for seven years. The novel’s plot mirrored its composition: it was first conceived as a novella, a lighthearted counterpart to the gloomy Death in Venice. But Mann began writing in 1913 and didn’t finish for more than a decade. Between those two points, the first world war radically changed the book’s size, scope and temper because it radically changed the political and moral outlook of its author.

Mann began the war a staunch conservative. Yet by the early 1920s he was making speeches in defence of the maligned Weimar Republic. (In time, and in exile, Mann became the most prominent German opponent of the Third Reich.)

This tumult fed into The Magic Mountain, notably in the characters of Lodovico Settembrini (humanist) and Leo Naphta (rightwing radical), who vie for Castorp’s soul. Their arguments are dazzling – far more so than the political toing and froing Mann engaged in while writing the novel. It isn’t Jensen’s intention, but his dogged account of Mann’s shifting political views supports the theory that a novel can know more than its creator.

Jensen falters occasionally when attempting to correct the record. He says the “oft-repeated claim” that Mann “was an indifferent or cruel parent seems inaccurate”. Yet all he offers in support is a single quote from the autobiography of Thomas’s son Klaus, who was deeply troubled for much of his relatively short life. There is voluminous evidence to the contrary.

Jensen also takes issue with the “callousness” of Ronald Hayman’s assertion, in his 1995 biography, that Mann “liked and admired” his wife but wasn’t in love with her. Hayman supports his claim by quoting from a letter Thomas wrote to his brother on the matter. It’s permissible to takeissue with Hayman’s conclusion, but Jensen’s protest – “How could he possibly know?” – seems disingenuous coming from a writer engaged in the same process of interpretative analysis. Especially in the case of a judgment about Mann (“gay most of the time”, in Colm Tóibín’s description) that is so uncontroversial.

Whatever the truth may be, it doesn’t make The Magic Mountain any less captivating an exploration of the human condition, or less of a literary achievement. Jensen doesn’t penetrate deeply into the mysteries of the book, but he doesn’t aim to do so. Rather, he gives a brisk, confident overview of an extremely dense work of art – no small achievement – and contextualises the era in which it was forged. In his foreword to the novel Mann wrote that “only thoroughness can be truly entertaining”, but summary has its pleasures too.

I thoroughly enjoyed your review of Morten Høi Jensen’s insights into Thomas Mann’s “The Magic Mountain.” Your exploration of contradictions in Mann’s work reminded me of my own journey through complex narratives in literature. I once wrestled with the themes in Dostoevsky’s novels, where moral dilemmas create a similar paradox. It might be interesting to delve deeper into how these contradictions reflect broader societal issues—perhaps even their relevance today. basketball stars 2026 What do you think about drawing more parallels to contemporary literature that also grapples with such dualities? Thank you for sparking this fascinating discussion!